I had come to Yale for graduate work, but Yale said I needed more music courses before they would accept me into the Master’s degree program. A good thing was that I already had a great deal of performance experience, and had a certain confidence and poise that helped me navigate a really heavy schedule of lessons and classes. I felt Bruce Simonds saw my potential, and he really laid it on, so to speak.

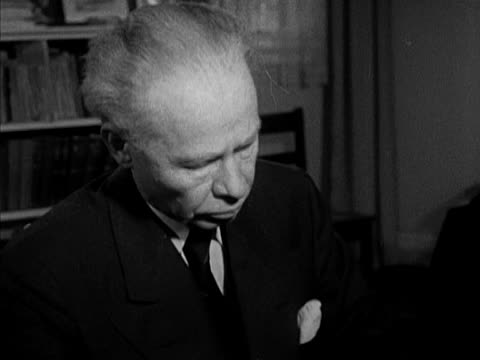

Bruce was rather old fashioned in many ways. He sat at his piano and rarely invaded your space at the other piano. The “lesson piano” was always a bit out of tune and rather rough. His piano always sounded perfect! He was a Steinway Artist and Steinway kept him well off in pianos, even at his home. He kept a black notebook, and wrote down comments about every lesson. He always would make some sort of mark at the end of the lesson, but I never managed to see what it was. It was probably a grade for that session.

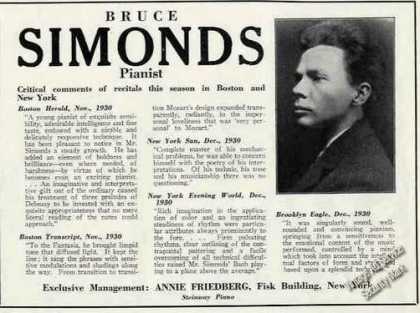

Bruce played so naturally I always felt he didn’t have to work hard. His wife, Rosalind, put me right in that category. She said he often had to practice late at night, and sometimes went past midnight. He could astonish. He came in to our Beethoven class and sat down at 9 AM and played the whole of the “Hammerklavier” from memory. No doubt he slept soundly before he did it!

Bruce had a way with words. I remember his description of the opening of the "Appassionata," “like a blank face,” or the opening of the Sarabande from Pour le piano … “think of holding a piece of sea green glass to the light!” He could also be a great actor. He made a scene out of playing Beethoven’s “Rage over the Lost Penny,” finally pulling one out of the piano strings with a wild look on his face. His party piece was Poe’s “The Raven,” set to a mawkish but very entertaining musical accompaniment. He could reduce a gathering to tears of laughter with this, but be moving at the same time. He was a born entertainer in concert and in life.

I never felt I was being overly organized technically, but Bruce did have a way of getting his ideas across. He had lots of little rules, which he dangled before you constantly. These seeped into your brain and slowly you began to change. He told me right off the bat that I made a nice sound, but I was far too tense. He made a great difference in my overall approach, but it was left to Hilda Dederich in London to really make me toe the mark with the Matthay technique.

What I do owe Bruce was his unfailing sense of artistry and the many ways he took to make me search out more depth and polish. Polish is what we did...polish, polish polish. I could hear the change coming over my sound and spirit. Even though he was a bit difficult to understand at times, one felt he had a definite plan for you.

It was odd that he never came back after you had played, rather, one had to wait until the next lesson to get the lowdown. He never talked about how to build a career, and in fact, most teachers in that era just taught you to a high level and let the rest fall into place. Bruce did say that he once played for Harold Bauer and he told Bruce his rhythm was not good enough for a career. When he did make his debut in Wigmore Hall, Mr. Matthay was over the moon, telling him he was “a great man.”

Looking back all these decades, I am grateful for all the practical experience I got at Yale, with two big solo recitals and concertos by several composers, two of which I played with the Yale Symphony. I even got chances to play off campus. We were supposed to ask permission to do that, but I am afraid I never did. I played for the Yale Alumni Men’s Chorus, and they asked me to do a solo group at their big concert in Woolsey Hall. Of course the critic came, and there was my review the next day in the paper. Bruce saw me in the hall and rather laughed it off, so pleased that I got through the Schumann Toccata with aplomb.

I returned often to New Haven, and always had a lesson or two. Bruce was as picky as ever, but much more of a personal friend at that stage. He gave me a pattern to follow in my own career, knowing full well one has to teach and perform to a high standard, as well as be ready for a lot of public service. He made me feel that was a high goal in life, and I am forever grateful to him.

Back to Matthay Home Page

Back to Matthay Home Page